Post by Mikael Svensson, Consultant and Strategic Advisor NHTA

Health Technology Assessments (HTAs) of new drugs, including or excluding CEA, are based on data on the drug’s treatment effect from clinical trial(s) with a typically rather short follow-up time. This means that it is often uncertain how effective the drug is over a longer-term period, which also makes it uncertain for HTA agencies to assess a “reasonable” price.

For example, we have shown in a study that around half of the newly reimbursed cancer drugs in Sweden have data supporting improvements in length or life and/or quality of life. For the other half of reimbursed cancer drugs, data is based on surrogate endpoints with more uncertain effects on longer-term final endpoints. In an earlier post, I have also summarized a new study that showed that the data cutoff time in a clinical trial can substantially impact how accurately long-term effectiveness is modelled. In rare disease settings, the HTA process may be even more challenging due to the reliance on small single-arm studies. In addition, for some gene therapies where there may be claims for a curative long-term effect – there will never be any clinical trial that can have long enough follow-up to verify such claims.

The trade-off between being “too conservative” or “too liberal”

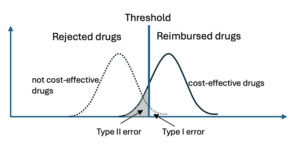

For the HTA agency, there is a trade-off between Type I and II errors when making reimbursement decisions for new drugs with uncertain benefits and cost-effectiveness. If we divide new drugs into 1) cost-effective and 2) not cost-effective drugs, there is some risk that a decision-maker will reimburse a drug that is not cost-effective because long-term effectiveness is overestimated (type I error), and another risk that a cost-effective drug will not be reimbursed if long-term effectiveness is underestimated (type II error). Uncertainty over long-term costs may have similar consequences.

There are various ways to address the uncertainty in long-term effectiveness. One approach is to set more stringent demands on producers (e.g., run longer and/or larger studies). This will reduce the risk of a Type I error, but it will also increase the risk of a Type II error. Thus, it is a delicate matter to find the appropriate balance. Another approach is to use Managed Entry Agreements (MEAs) that may require the producer to verify evidence after certain set time points or using payment models that link payments to patients reaching certain set outcomes. This sounds good in theory, but often comes with several practical challenges.

How HTA agencies address uncertainty

In a new study by Versteeg et al., the authors analysed how a number of HTA agencies dealt with the uncertainty around long-term effectiveness, especially how various managed entry agreements (MEAs) or conditional reimbursements were used. The study focused on the experiences related to 9 drugs targeting Spinal Muscular Dystrophy (SMA), Cystic Fibrosis (CF), and Hypercholesterolemia (HC: high cholesterol) from HTA agencies/organizations in six countries (Netherlands, England, France, Germany, Canada, and the US).

The authors concluded that long-term uncertainty was generally considered in more or less all cost-effectiveness analyses by the agencies (when such were conducted), and in about ¾ of the comparative clinical assessments. Only the Dutch HTA agency did not explicitly outline long-term uncertainty as an important consideration in all of their CEAs. However, it was also found that there were important differences in which type of trial data was considered relevant for inclusion in the assessments (depending on the trial length of follow-up). For example, the agencies had substantially varying views in accepting open-label extensions as valid evidence for long-term data.

In terms of MEAs, this was most commonly suggested for SMA drugs, and included outcomes-based (e.g., pay for performance) and financial-based agreements. For CF and HC drugs, there were fewer MEAs suggested, and the ones suggested were “simpler” financial-based agreements. HTA agencies in the Netherlands and Canada were more likely to suggest MEAs than the French and English agencies, although differences were not that substantial. The German and US HTA agencies do not have such objectives in their mandate and were excluded from MEA considerations. Reassessments based on updated data were also relatively frequent, especially by the French agency, in about half of the cases.

Summing up

The results indicate substantial variation in specific preferences and “acceptance” of uncertainties across HTA agencies and that such preferences can impact the final reimbursement decision. The authors also highlight that it may be important for HTA agencies to align their preferences to facilitate pharmaceutical companies designing trials and data collection accepted by as many agencies as possible. On the other hand, is such alignment desirable if differences across HTA agencies reflect actual differences in a country’s preference for “risk-taking”? However, several methodological differences across HTA agencies likely do not really reflect actual preference differences across populations. The challenge is finding out which differences are well-motivated…